When I first started learning woodworking, an older craftsman once showed me a workbench that was older than both of us. He tapped one corner and said, “That joint has lasted generations because it was the proper way to do it.” He was referring to a mortise and tenon.

It’s that single moment which explains why this joint still matters today. Mortise and tenon joints don’t care about speed or shortcuts.

They are about strength, balance and constructing things that endure. If you prefer furniture where the joint remains solid for decades, rather than wobbling after a year, this is the one.

What Is a Mortise and Tenon Joint?

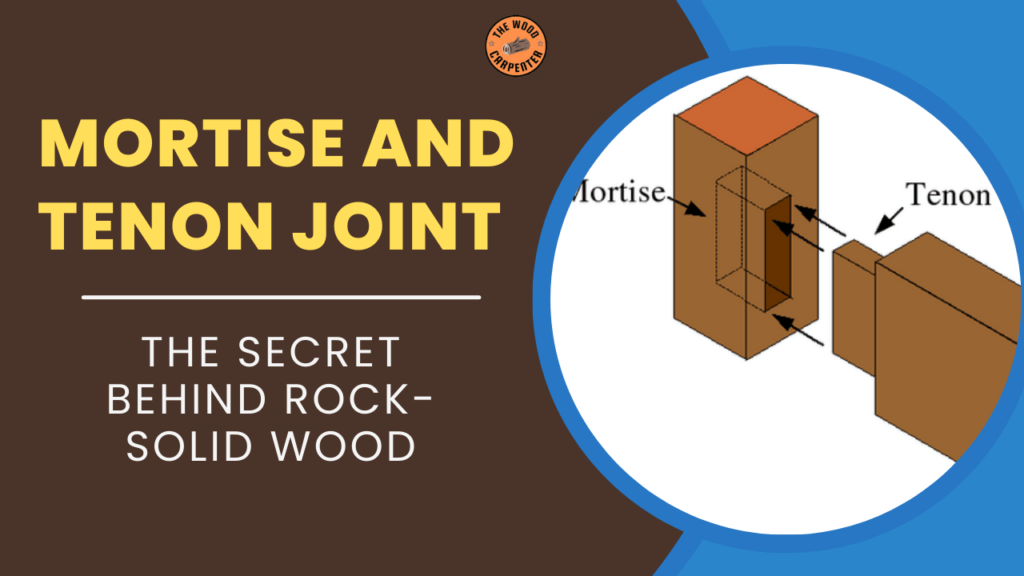

A mortise and tenon joint is where you join two pieces of wood together based on shape instead of relying on metal connectors such as a nut and bolt or screw.

One of the pieces of wood is with hole. This hole is known as the mortise.

The second piece has a cut out tongue-like extension at one end. This piece is known as the tenon.

The tenon is inserted into the mortise, where it should fit snugly as if into a lock. And if done well, the joint becomes very strong, since a great deal of wood contacts wood. It’s even possible to add glue, pegs or wedges, although the real strength comes from the fit.

Unlike a screw or nail, this joint relies on the direction of wood grain and the surface area in contact. In fact in many instances, these joints are stronger than the wood surrounding them.

Why Mortise and Tenon Joints Still Matter Today

Walk a museum filled with ancient furniture or historic homes and you’ll see mortise and tenon joints everywhere. The Egyptians in antiquity incorporated them into ships and furniture. Medieval craftsmen employed them in timber frames and churches. Many of that era’s buildings still exist.

Modern furniture often uses faster methods like dowels, biscuits, or pocket screws. These methods work, but they do not match the long-term strength of mortise and tenon joinery. This joint resists twisting, pulling, and side pressure better than most alternatives.

One reason it endures is in the way it deals with wood movement. The wood in the mortise and tenon joint tends to swell or shrink with changes in humidity, which will alter the tightness of a well-fitted joint. That built-in flexibility is one of the reasons heirloom furniture endures generation after generation.

Where Mortise and Tenon Joints Are Commonly Used

This joint appears wherever strength and stability are important.

Furniture makers use it in tables, chairs, beds, and benches to prevent wobbling.

Cabinetmakers rely on it for frame-and-panel doors so they stay square over time.

Wooden doors and windows use it to resist sagging and twisting.

Workbenches depend on it to handle heavy pounding and clamping forces.

Timber framing uses large mortise and tenon joints to hold entire buildings together.

Outdoor furniture and garden structures use wedged versions that remain strong even when glue fails.

If a joint must carry weight or survive constant use, this method is often the best choice.

Types of Mortise and Tenon Joints

Although the basic idea stays the same, woodworkers adjust the joint to suit different needs. Below is a clear comparison of the most common types.

| Type | Description | Best For | Strength Level |

| Through | Tenon passes fully through the mortise and remains visible | Timber frames, rustic furniture | High |

| Blind (Stub) | Tenon stops inside the mortise and stays hidden | Cabinets, fine furniture | Moderate |

| Wedged | Wedges expand the tenon inside the mortise | Exposed or outdoor joinery | Very High |

| Haunched | Extra section on the tenon prevents twisting | Doors, window frames | Very High |

| Twin (Double) | Two narrow tenons instead of one wide one | Wide rails, heavy furniture | Very High |

| Fox-Tail (Secret) | Hidden internal wedges for clean appearance | Fine concealed joinery | Moderate |

Wedged through-tenons usually rank highest in strength because the wedges lock the joint mechanically.

The Haunched Mortise and Tenon Explained Simply

The haunched mortise and tenon is especially important for doors and frames.

It includes a small extra section at the top of the tenon. This fills the groove used for panels and prevents twisting at the joint. Without the haunch, doors would slowly sag and gaps would appear at the corners.

That is why cabinet doors, window frames, and traditional panel doors almost always use this variation.

How to Cut a Mortise and Tenon Joint

Making this joint takes patience, but the steps are straightforward.

Most woodworkers start by cutting the mortise first because it is harder to change later. The mortise is usually centered in the thickness of the wood and is about one-third the wood’s thickness.

The waste is removed slowly using chisels, drills, routers, or mortising machines. The key is keeping the mortise walls straight and square.

Once the mortise is finished, the tenon is cut to match it exactly. The tenon cheeks define the thickness, while the shoulders help pull the joint tight and keep everything aligned.

A good test fit slides together with firm hand pressure. If it needs a hammer, it is too tight. If it feels loose, the joint will be weak.

Gluing and Assembly Tips

Glue should be applied evenly to both the mortise walls and tenon faces. Too much glue does not add strength and only makes cleanup harder.

After assembly, the joint should close fully with clamp pressure, and the shoulders should sit flush. Checking for square immediately is important because adjustments are difficult once the glue begins to set.

For wedged through-tenons, the wedges are usually added after the glue has partially set to avoid splitting the mortise.

Common Mistakes Beginners Make

Many beginners cut the tenon first. This makes fitting difficult. Cutting the mortise first gives you a fixed target.

Another mistake is ignoring grain direction. The tenon grain must run lengthwise. Cross-grain tenons break easily.

Dull tools also cause problems. Clean cuts make tight joints. Torn fibers weaken the glue bond.

Rushing the fitting process is another issue. The strongest joints come from slow test-fitting and careful trimming.

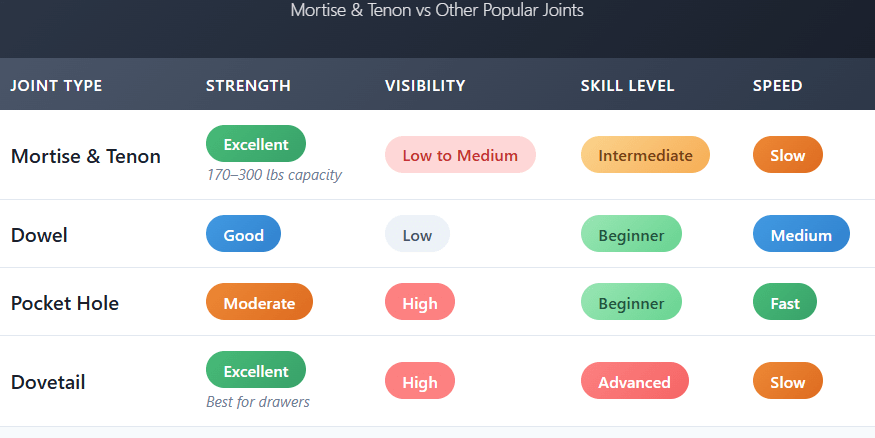

Mortise and Tenon vs Other Joints

Mortise and tenon joints outperform dowels and pocket screws in load tests, especially in frames and furniture that face constant stress.

Advantages and Disadvantages

The biggest advantage of mortise and tenon joints is strength. They distribute stress across a wide area and resist twisting and pulling better than most joints. They also last a very long time and do not rely on metal fasteners.

The downside is time and skill. These joints take longer to make and require accuracy. Mistakes are harder to fix, and beginners need practice. For fast projects, modern joinery may be easier.

Modern Uses and Variations

Today, the joint remains in common use, even with advanced techniques. CNC machines and routers now cut mortise and tenon joints for production furniture. Floating or loose tenons, such as those made with domino-style tools, speed up the process while keeping much of the strength.

Timber framers continue to scale the joint up for barns and houses, proving that the same idea works from small stools to full buildings.

Frequently Asked Questions

How strong is a mortise and tenon joint?

A well-made joint can handle several hundred pounds of force and often fails only when the surrounding wood breaks.

What is the ideal mortise size?

The common rule is one-third the thickness of the wood, which balances strength and safety.

Can beginners make this joint without expensive tools?

Yes. Chisels, a saw, and careful layout are enough. Power tools only save time.

Which wood works best?

Hardwoods like oak, maple, ash, and walnut hold crisp joints well, but softwoods also work with care.

Final Thoughts

Mortise and tenon joinery is not just a method. It is a mindset. It requires patience , accuracy and respect for materials.

Your early joints may not be perfect, and that is part of learning. With practice, the fit improves, your confidence grows, and your furniture becomes stronger and more reliable.

Now this joint has been around for thousands of years for one reason—it works. Master it and you have the foundation for that supports a lifetime of quality woodworking.